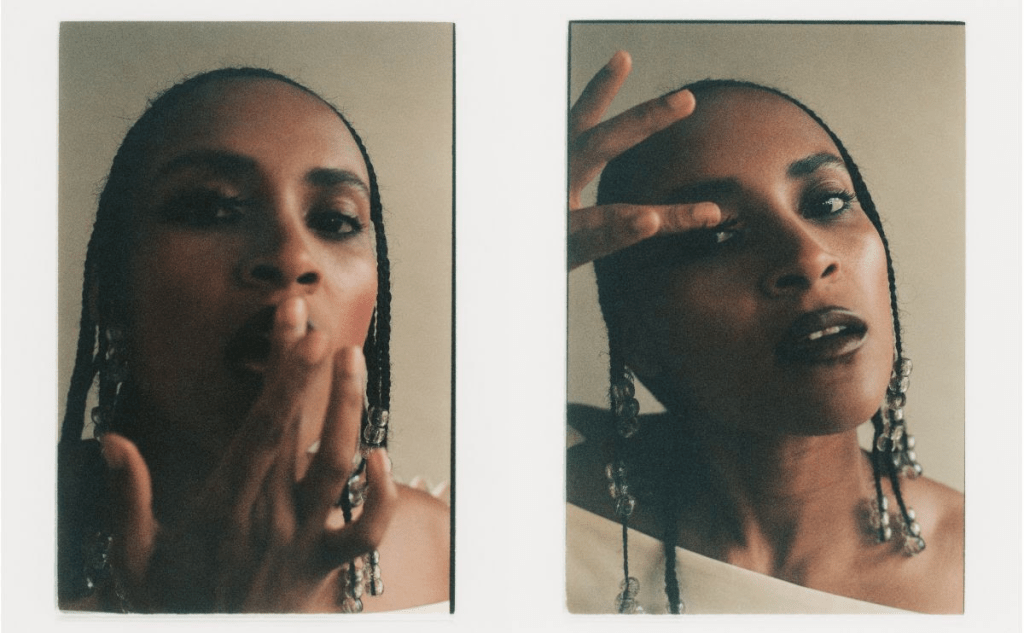

The Montreal-based multi-instrumentalist’s discusses how the cyclical nature of life inspired her alluring full-length debut.

By: Sun Noor

Ouri’s musicianship knows no bounds and her new record out today, Frame of a Fauna, is a testament to her ever-evolving creative vision. The multifaceted artist’s album arrives merely a few months after the release of Hildegard, a stunning, eponymous offering that marked the beginning of her creative partnership with singer-songwriter Helena Deland. The project came together in a matter of eight days as a result of sonic experiments that showcase the duo’s collective strengths. Ouri’s new release captures her distinct artistry. From start to finish, the emotive record presents a captivating collection of eclectic sounds that emphasize its underlying current of transformation.

I caught up with Ouri a few days prior to the album’s release to peel back the layers of her œuvre.

You’re about to release your full length debut record, Frame of a Fauna, in a few days. How are you feeling about that?

“I feel super excited. It’s the first time I’m actually like so happy with what I did. I can wait to have people’s opinions and reactions to it and see what resonated most.”

Yeah, I had a chance to listen to it a few times, and it’s like, a very beautiful record. I felt like it was like a transcending experience. As a multifaceted artist, how do you know when an album or like an idea is completely finished?

“I feel like with this album, it was like on different levels. It was sonically, it had to be complete, it had to show a spectrum of diverse things. It’s like also closing a chapter of your life so it all has to make sense at the same time. Then, it’s like, complete. Sometimes it’s just like this feeling, you know that it’s done. Sometimes you never get that feeling. You feel like you could always work more. You have to realize that you want some idea to be conveyed. If it’s the case, then you should stop. You should try to go somewhere else it can be influenced.”

You compared making this album to opening your brain and removing unwanted parts. That’s a really big statement. How was the entire process?

“First, I wanted to isolate myself in a sea that I was not familiar with so I could really step away from the kind of character that you become. You know, you’re always available for the people that you love, and you’re not being just the artist part of yourself. So I started by isolating myself in this way. I was just like listening (to the album) again and again and realizing where I was not 100% authentic. I cut those parts and replace them with something else.”

“Also, through this year of making this album, I started therapy, so it was like literally picking things to take out of my brain. That was the first time I was doing therapy and I loved it. It changed my life and I was afraid it would make me less musical or something, but it actually just helped me dive into the music more.”

I really like how the album has many layers sonically. There are lots of textures and moods connected together. Everything connects and flows so well. How did the idea around the cycle of life manifest for you?

“It was not in my control. Actually, it started when my sister had her baby, and I wanted to be there because I’m so close to her and to witness this new person in my family. So I started the album, coming to Europe, being close to my sister, and it ended when my mother died. I could not feel like the album was complete before that. Then, I realized that it started with my family and it was going to end with it. The last song (“Grip”) was going to be about someone of my family that I just lost. I realized that it was really about shaping oneself but also, entering the world and leaving the world. It kind of all made sense at the very end.”

Do you feel like exposing like yourself in a vulnerable states sometimes adds to your art?

“Yeah, I think we feel most touched by art that is like showing someone’s vulnerability, even if it’s just like 5%. If that 5% of vulnerability is real, the connection that the audience is going to have is much stronger, I find. Sometimes it’s too much. You know, you cannot just show your vulnerability and like put all the power in someone else’s hand. You have to create a structure, and then put your vulnerability in the middle, then create a nest for it.

You worked on this album in like different places as well. Does being in different settings help with your creativity?

“Yes, definitely. I was really in research and demo mode in London. Then I went to Berlin by recorded a bunch of stuff and was thinking more about the community, like people that I wanted to feature on my album. Then finishing in Montreal, I feel like Montreal for me is a place where I become super strict and severe. I have this really judgmental approach. So use this place to finish projects more than start them sometimes. You know, use different places for different stages of the process helps.

When you’re stuck on an idea, what do you do to get yourself out of the rut. What is your process?

“First is to take a break. Second, use psychedelics. Third to show it to someone else and have their opinion on it. Sometimes people from the outside, the people who really know you, can see where you’re getting stuck. So it can help too.”

Was there a particular song that you felt very stuck with in the beginning, or did everything kind of just flow together seamlessly?

“The first track, “Ossature,” made me feel like I knew exactly what the whole spectrum of the album would be like. It was actually the last song that I finished. I could not finish it, I was playing with it, because I thought it was too soft, and then it was too hard. I had to incorporate new drums, it went in all directions. Finally, it was the last track finished on the album even though it was the first one that started the whole thing.”

As a multi- instrumentalist who plays both the cello and harp, do you usually improvise or work like a structured idea during your writing process?

“It depends, sometimes I’m just playing with sounds, and then they become harmonies, and a progression of chords. Sometimes I just wake up and I have this urge to just sing. I record myself and just sing the whole song with all the lyrics and it’s just like the first time. Then, I work a structure around it. It really depends. I feel like it’s nice to never start songs the same way so you never know how it’s gonna end. You’re really connected to what’s happening between your hands.”

Would you say that not limiting yourself makes for the best art?

“Sometimes, it depends. At the very beginning, it’s really nice to have no limits, but soon enough, I think it’s nice to have some sort of structure. It’s an art that you know happens alone or with a few people in the studio, then it’s meant to be listened to by a bunch of people that you don’t know.”

“It’s nice to just think about how this music is gonna be translated in different environments, and then you really need to structure yourself. Freedom is important, that control is important too in a way. I don’t want have no consistency or be so controlled that there’s no diversity in the project. Feels a little bit like mechanical or dead.”

It’s good to have balance. In a few words, how would you describe this album?

“I feel like it’s an album of fusion of styles and sounds and it’s really incarnated in a way, it’s very physical and sort of down tempo. Even the fastest moments are still like slow in a way. I would say it’s a slow album.”

What are your favorite albums at the moment?

“I really like Yameii Online, Slausone Malone 1’s Vergangenheitsbewältigung (Crater Speak). Also I’m always listening to Jaco Pastorius, it’s like more old school bass and jazz. I discovered Sam Gendel, who did a collab with Moses Sumney. It was super cool, they did, like a remix of T-Pain (“Can’t Believe It”).”

Ouri’s debut album, Frame of a Fauna, is now available on all streaming platforms.